THIS ALBUM IS A PART OF GERMAN HISTORY AND IS NOT FOR PROPAGANDA PURPOSES.

Quick answer (key takeaways)

- You’re looking at a mid‑20th‑century photo album from the VEB Kalibetrieb “Südharz,” Werk Volkenroda (district of Mühlhausen) in the Deutsche Demokratische Republik (GDR/DDR). “Kali” means potash; this plant mined and refined potassium salts (KCl) for fertilizer.

- The images trace a complete ecosystem: the shafts and headframes, underground machinery, processing halls, rail and coal handling, rescue and health services, training, culture clubs, sports, a union library, and even holiday homes.

- Industrial photos like these are not just about machines. They encode how people moved, learned, celebrated, and were cared for in a planned economy. Look for faces, signs, room layouts, and the way streets and conveyor bridges connect buildings.

- The album’s tone is purposeful and proud, with well‑composed shots that highlight order and completeness—a classic of enterprise albums across the Eastern bloc.

- If you read them closely, the photos double as a guide to how potash traveled from a salt seam underground to fields across Europe and how a mine was also a community anchor.

What this article covers

- A friendly walk‑through of the album, picture by picture, with what to notice.

- How potash mining worked here, from geology to bagged product.

- Cultural notes that place each scene in everyday DDR life.

- Answers to common questions about VEBs, potash, and the social world around a mine.

Context: Where we are and why it mattered

The second page of the album spells it out in careful block letters: VEB Kalibetrieb “Südharz,” Werk Volkenroda, Kreis Mühlhausen. VEB stands for Volkseigener Betrieb—people-owned enterprise—state companies in the DDR. Südharz points to the southern rim of the Harz mountains, a long‑worked potash basin. Potassium chloride (KCl) was strategic. A country that prized self‑sufficiency needed fertilizer to raise yields; potash was also a valuable export that brought in hard currency.

The album cover—blue with gold geometric lines—already hints at care. This isn’t a random stack of snapshots but a presentation piece, the kind a plant might show to visiting delegations, apprentices, or newly elected union officials. Let’s open it and step through.

- Panorama and approach: the industrial landscape. A spread with two landscape photographs introduces the site. In the wide shot, a cinder‑colored spoil heap rises like a new hill beside chimneys and a boxy headframe. The cloud ceiling is low, the light silvery—good conditions for the crisp, evenly exposed industrial images favored by staff photographers. In the narrower view, a steel shaft tower leans across the frame, a conveyor stretching from the head to processing buildings. You can almost hear clanking rollers and air gently hissing from compressed‑air lines.

What to look for

- The hierarchies of height: headframes and chimneys dominate; low processing sheds and tracks run beside them. This tells you which functions had to be tall (hoisting, exhaust) and which spread out (crushing, flotation).

- The spoil tip, sharply terraced, reveals years of production. Each layer is a timeline in rock.

- Arrival point: buses, the Kaue, and the social building

“Blick auf den Busbahnhof – Im Hintergrund die Kaue und das Sozialgebäude.” Workers arrive in rounded, two‑tone buses that look like postwar designs updated into the 1960s. People step down in dark coats and caps, moving with a practiced gait. The background building is the Kaue, miners’ changing house. In German mines, a Kaue is instantly recognizable if you can peek inside: clothing baskets hang from the ceiling on chains and are winched up to dry. Next to it is the Sozialgebäude—the social building with showers, lockers, ca anteen, and offices.

Cultural note

Company buses were ordinary. Many mines sat outside town centers; scheduled lines tied shift change to home life. That choreography—a bright bus pulling up under a gray headframe—was the DDR’s morning heartbeat in mining districts.

- Underground, where the ore begins

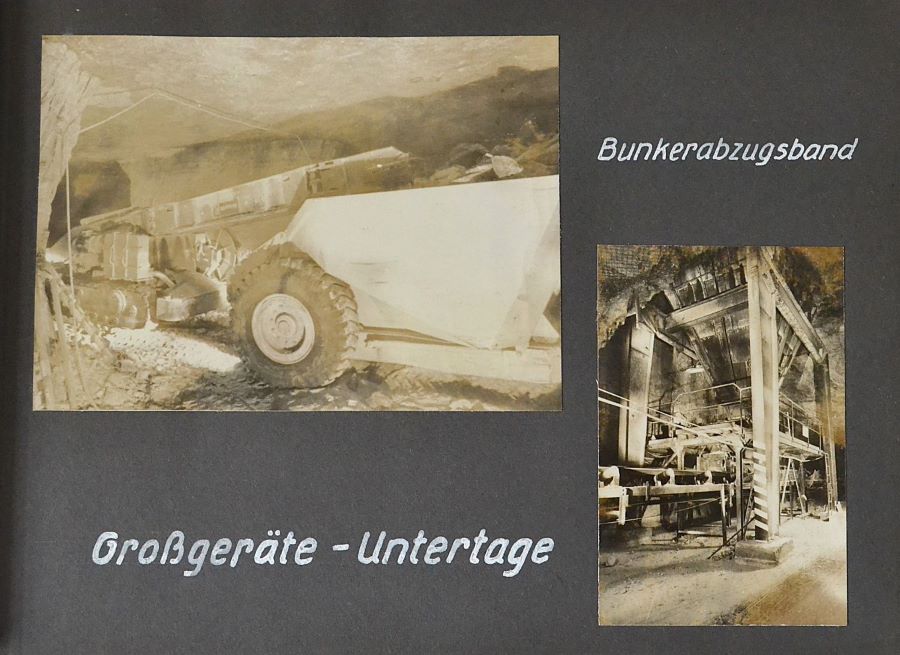

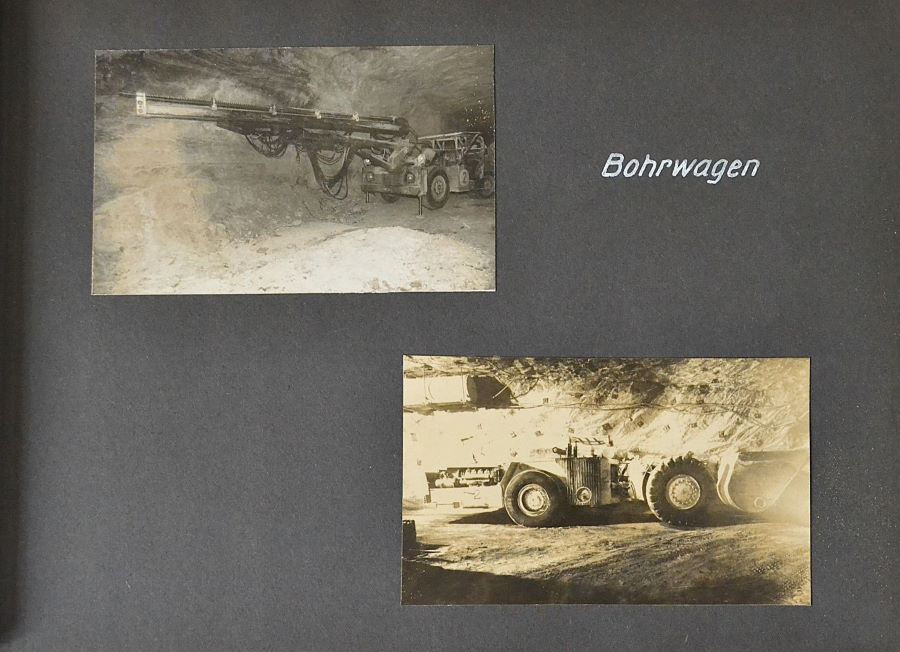

“Großgeräte – Untertage” shows a low, muscular vehicle with wide tires and a bucket—the classic underground loader or dump truck. The ceiling is chalky and close; ventilator tubing snakes at the edge of the frame. In the facing photo, “Bunkerabzugsband,” a bunker discharge conveyor under an underground storage bin funnels broken ore to belts. Nearby, “Bohrwagen” features a drill jumbo with multiple booms, its long feeds pointed at the face.

What to look for

- The scalloped roof marks room‑and‑pillar mining, common in potash. Thick pillars hold the roof; rooms are cut in a grid, giving those cathedral‑like underground avenues.

- The equipment is compact and articulated for tight spaces, with low exhaust and dust suppression—details a photographer might emphasize to suggest modernity and safety.

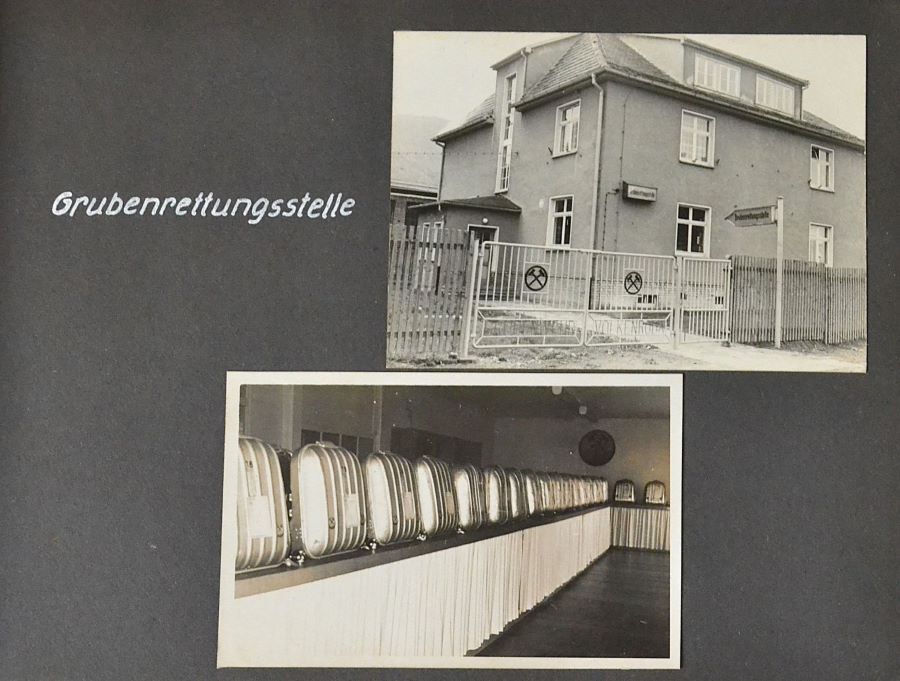

- Safety as a system

“Grubenrettungsstelle.” Outside, a cleanly fenced service house carries the crossed hammer and pick symbol. Inside, a long line of polished breathing apparatus sits like silver beetles on a skirted bench. It’s meant to be reassuring. Every mine contends with gas, smoke, and the unexpected. The rescue station photo—meticulously arranged devices, a clock on the wall—signals readiness.

Cultural note

The DDR placed visible emphasis on safety committees and rescue brigades. Displays like this were part functional, part didactic: they showed apprentices and visitors that safety was formal, standardized, and inspected.

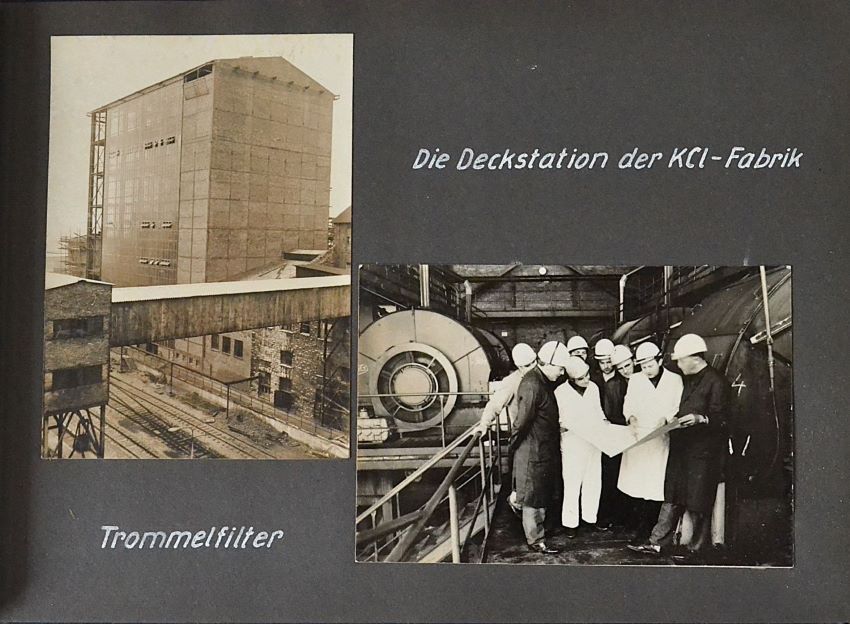

- From rock to product: the KCl plant

Turn the page, and you’re in a big process industry. “Die Deckstation der KCl‑Fabrik” und “Trommelfilter” anchor the spread. Outside, a high, window‑latticed building rises above rail lines and a covered conveyor bridge, making a steel and glass canyon. Inside, a group of men in lab coats and hard hats cluster over a drawing between cylindrical vessels—drum filters used to separate brine from crystal.

How the plant worked (simplified)

- Crushing and dissolving: Potash ore is crushed and brined.

- Separation: Insolubles settle out; a hot‑cold crystallization sequence forms KCl crystals.

- Filtration and drying: Trommel filters and centrifuges separate mother liquor from crystals; dryers finish the job.

- Screening and bagging: Product is sized and bagged or shipped in bulk.

- The photos were chosen with clean, symmetric angles. Handrails align with machine flanges; workers’ coats contrast with dark steel. It is a visual language of competence.

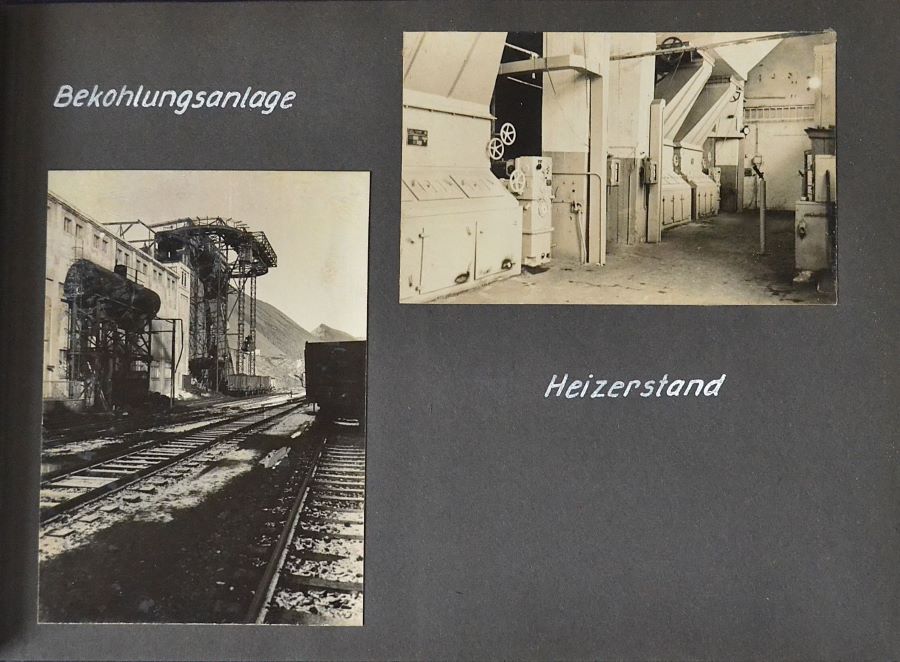

- Energy and motion: coal handling and the boiler hall

“Bekohlungsanlage” shows a skeletal gantry alongside parallel tracks. A coal bunker, pipework, and the long wall of a boiler house align with a coal tip behind them. “Heizerstand” brings us inside to the stoker’s gallery—valve wheels, hoppers, a tiled floor swept clean. In these images, the plant is both muscle and skeleton; energy systems are the ribs that keep every drum turning, every fan spinning.

Cultural footnote

The DDR relentlessly photographed machinery rooms. It wasn’t just propaganda; operators were proud of spotless stations. An immaculate Heizerstand meant better inspections, fewer unplanned outages, and a sense that an engineer could bring a visiting student here without apology.

- Social architecture: where people met, ate, and rested

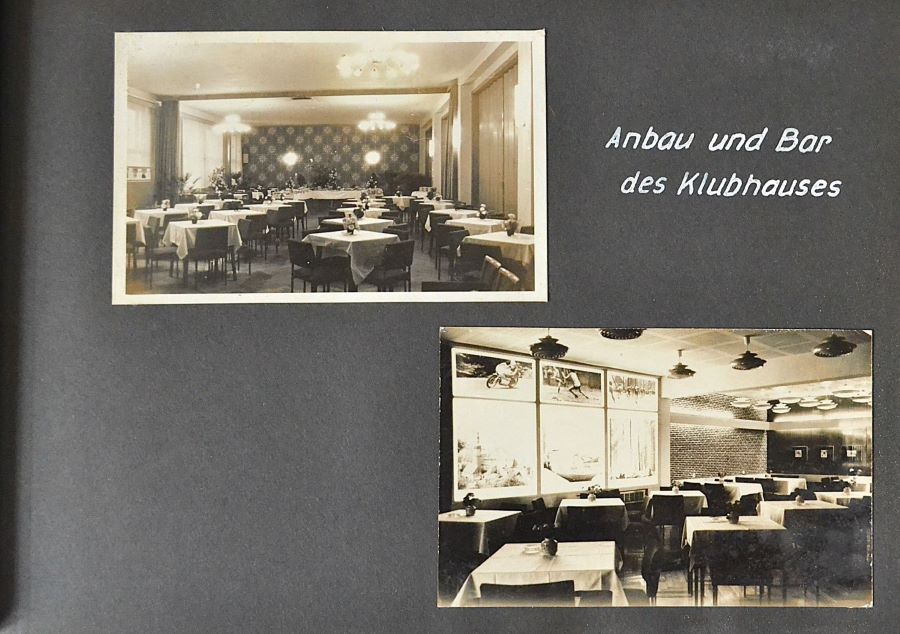

The album spends real time on interiors. “Inneneinrichtungen der Sozialgebäude” gives two dining rooms—one in Volkenroda, the other in Pöthen—filled with light, plants on stands, and a mural of an industrial panorama. Later, “Anbau und Bar des Klubhauses” shows a refreshed hall with patterned wallpaper and a bright corner bar under circular light fixtures. All tables have tablecloths and small vases. This is not incidental: in the DDR, the Kulturhaus or Klubhaus served as a village’s living room. After shifts, workers met for lectures, dances, or film nights.

Look at the faces

In the candid cultural competition shots—“Brigaden im kulturellen Leistungsvergleich”—performers grin mid‑routine, one person balanced on another’s hands; in another, a guitarist leads a choir. The expressions are concentrated and warm, a little nervous before an audience, then open as a song lands. These are the moments where an industrial album becomes human.

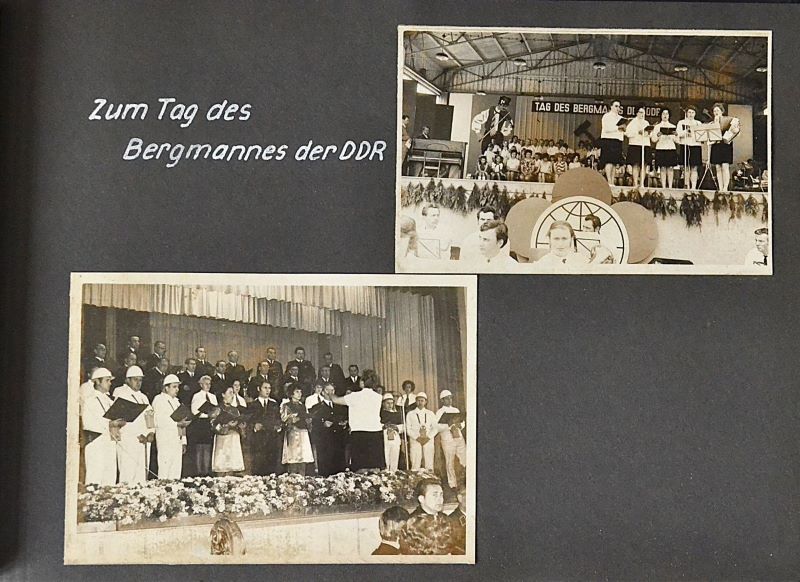

Rituals and remembrance: the Day of the Miner

“Zum Tag des Bergmannes der DDR.” The stage carries garlands and banners; on it, a chorus in dark suits stands beside people in white mining coats and helmets. The Day of the Miner was both a holiday and an affirmation, a thank‑you to a profession that shouldered risk for the rest of the economy. The photographer catches a conductor mid‑gesture. In the crowd, faces tilt upward—the shared attention that makes a ceremony work.

Learning to keep the plant running

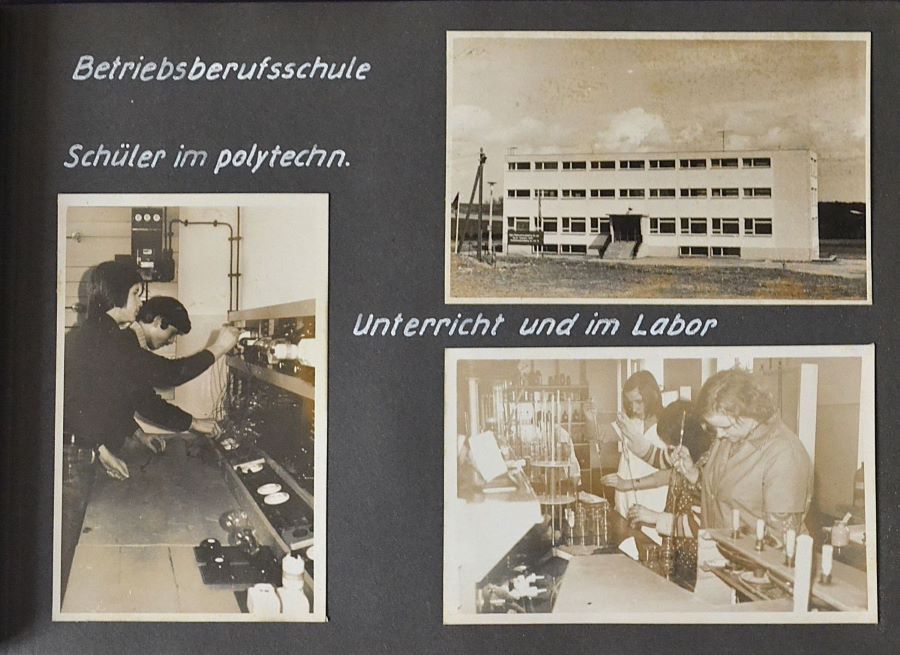

Education is another thread. “Betriebsberufsschule” shows a long, four‑story training school. Inside, “Schüler im polytechn.” and “Unterricht und im Labor” take us to a bench of switches and meters where two students adjust connections, and to a chemistry lab where young women handle pipettes and volumetric flasks. The DDR’s polytechnical education aimed to blur the line between theory and practice early; apprentices could be wiring a motor one week and learning solubility curves the next. The photo sequence stitches those worlds together.

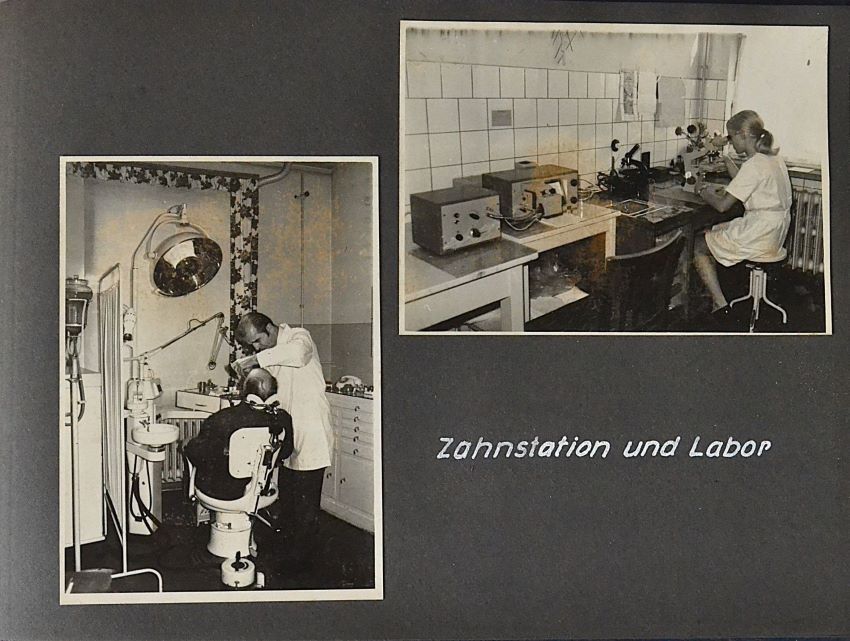

Health and care: clinic, dental station, and rescue

“Das Betriebsambulatorium” presents a modest, clean clinic building and a nurse gently holding the wrist of a patient on a tiled bed while a cuff inflates. It’s mundane, which is the point: routine care prevents crises. “Zahnstation und Labor” rounds it out with a dentist at a chair and a technician at a bench under neat shelves of glassware and instruments. Industrial work is rough on bodies. These rooms were part of doing the job.

Leisure and recovery: pool, sport, bowling, holidays

The plant didn’t stop at clinics. “Das Schwimmbad der Bergarbeitergemeinde” captures a bright summer day at a pool, crowded but orderly, children in swim caps at the edge, and one diver caught upside‑down off a board. “Der Sportplatz und die Kegelbahn” pairs a windswept field with an indoor bowling alley, a bowler in mid‑stride, “Sport frei!” lettered above the pins. The phrase, common throughout the German democratic sports movement, echoed discipline and joy. Finally, “Betriebs- und Kinderferienheim in Pappritz bei Dresden” shows a long, simple holiday building and a cheerful dining room. Workers’ children met peers there; forests around Pappritz offered hikes and quiet after months underground.

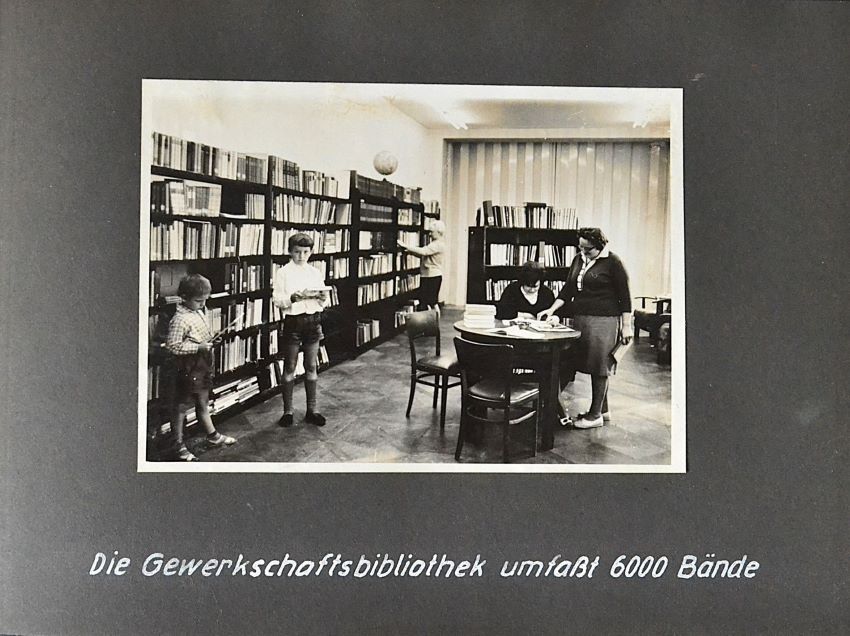

The library and the idea of self‑improvement

“The Gewerkschaftsbibliothek umfasst 6000 Bände.” In a bright room, shelves run the walls. A child stands reading; a woman points out a title to someone at a small table. The number matters—6,000 volumes—but so does the mix of readers. Union libraries combined technical manuals with novels, history, and geography. They encouraged a habit of reading that served both productivity and private imagination.

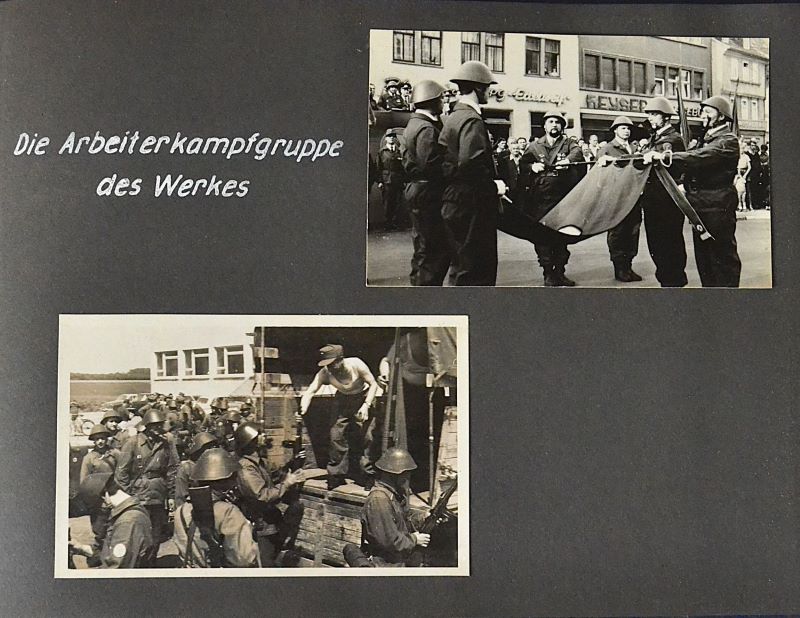

The Arbeiterkampfgruppe: a reminder of the Cold War

“Die Arbeiterkampfgruppe des Werkes” zeigt helmeted men drilling and distributing equipment. It is easy to forget, looking at cheerful pool scenes, that the DDR sat in a tense Europe. These workplace militias were tasked with civil defense and order in emergencies. Their inclusion in the album was routine; it placed the plant within the state’s broader security framework.

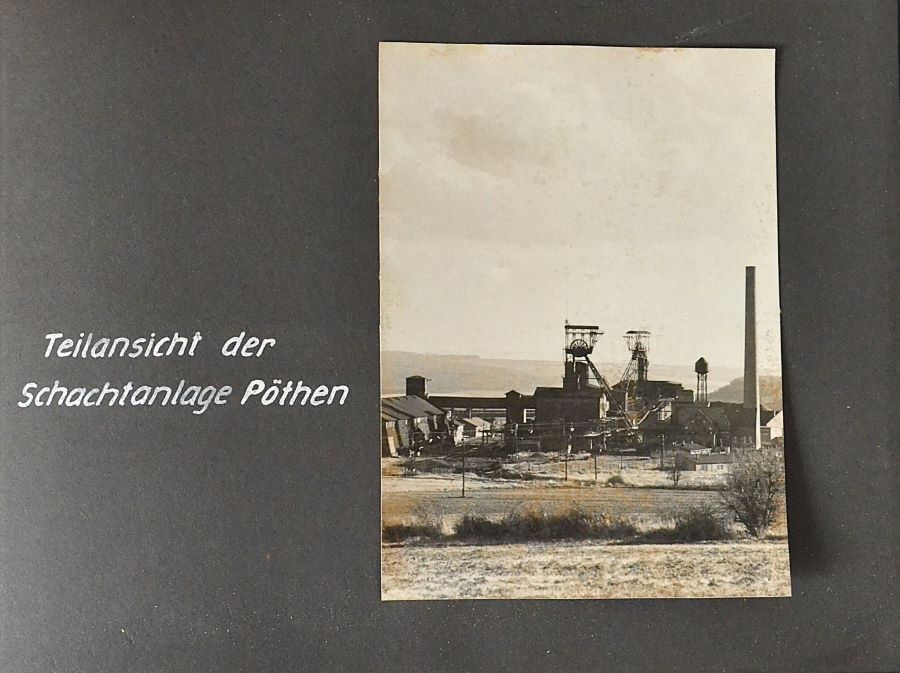

A last look at the shaft complex

“Teilansicht der Schachtanlage Pöthen” closes the industrial circuit with another look at headframes and chimneys against a low horizon. The photos don’t try for drama; they offer a straightforward portrait that lets an engineer identify buildings and flows. The quietness is respectful.

How to read industrial photos like these

- Follow the flow. Start at the headframe, trace conveyors, look for tall crystallizers or filters, and end at the rail spur or loading hall.

- Watch how people stand. In control rooms, bodies lean in; in ceremonies, they open up; in sports, they’re loose. Each posture tells you whether the moment is productive, celebratory, or restorative.

- Read the signs. Hand‑painted captions in the album are precise: Kaue, Sozialgebäude, Trommelfilter, Heizerstand. They fix terminology and offer a mini‑glossary of a mine’s universe.

- Note the furniture and finishes. Tiled walls signal hygiene spaces; patterned wallpaper and drapes mark social rooms; raw concrete and metal are for energy and material handling. In the DDR, interior design mirrored function with an almost didactic clarity.

- Count the connectors. Bridges, pipes, covered conveyors, and tracks are the circulatory system—each a clue to process and scale.

A concise primer on potash and why the DDR cared

Potash is a potassium‑bearing salt, often sylvite (KCl), in a rock called potash ore. Farmers need potassium to help plants regulate water and enzyme activity. Without it, yields drop, stalks weaken, and resistance to disease falls. In a country aiming for food security, fertilizer was a national strategy. The Südharz mines tapped layered salt beds laid down by ancient evaporating seas. By the 20th century, room‑and‑pillar methods and underground conveyor networks made it possible to move thousands of tons per day from face to surface. The photos’ trommel filters and tall process buildings show a mature, continuous operation.

Culture, pride, and the friendly tone of the album

Look again at the group around the blueprint by the drum filters. No one looks at the camera. They are all focused on the plan. It’s a subtle message: we are builders who talk to each other, not to the lens. Elsewhere, in the clubhouse, small centerpieces and neatly aligned chairs communicate hospitality. The Day of the Miner scenes carry gravitas, but also warmth—someone has pinned a garland just so, the stage is crowded, and the conductor’s sleeve is rolled to the elbow. The union library picture might be the quietest: a child reading next to an adult who is probably choosing a technical manual for a night class. Friendly is not an adjective printed anywhere, but it’s there in the choices: to include the bar, the bowling alley, the holiday home, and the clinic, alongside conveyor belts and drills.

What we don’t see, and why that matters

There are no accident scenes, no smoky shifts, no queues for scarce goods. Official albums highlighted the ideal—clean stations, welcoming canteens, smiling choirs. Yet the underlying infrastructure is real and specific. Even if the photos omit hardship, they capture a genuine completeness: an enterprise that was also a social provider. In that sense, they are honest about priorities if not about every difficulty.

FAQ

What is a VEB?

A VEB (Volkseigener Betrieb) was a people-owned enterprise in the DDR. Profits went to the state; managers and workers were bound by production plans. Many VEBs, like this Kalibetrieb, built social infrastructure—housing, clinics, culture houses—around their core function.

What is potash used for?

Primarily as fertilizer. Potassium chloride (KCl) supplies potassium, one of the three essential plant nutrients along with nitrogen and phosphorus. It improves yield, water use, and disease resistance. Some potash also goes into chemical and industrial processes.

How did miners get to and from work?

The album’s bus terminal photo shows dedicated routes that matched shift change. Workers often showered in the Kaue before riding home. The Kaue raised baskets of clothing to the ceiling to dry between shifts—an ingenious, low‑tech solution.

Was safety taken seriously?

Mines are hazardous, and safety cultures vary by time and place. Here, the rescue station, ordered apparatus, and training suggest a formal approach. The presence of clinics and a dental station rounds out that picture. The album, of course, shows the best face, but the infrastructure is there.

Why so much culture and sport?

In the DDR, workplaces were community hubs. Choirs, theater troupes, sports clubs, and reading circles met under the roof of the Kulturhaus or Klubhaus. Competitions between brigades—work teams—encouraged participation and pride. The photos of performances, bowls, and the pool speak to that policy turning into routine daily life.

How big was this operation?

The panorama, multiple headframes, tall processing building, and extensive rail lines indicate a sizable surface plant connected to a broad underground grid. The spoil tip’s scale suggests a long‑lived mine. Exact tonnages would require records, but everything points to a regional anchor.

A short glossary of terms in the captions

- Kaue: Miners’ changing room with hoisted baskets for clothes.

- Sozialgebäude: Social building for canteen, showers, and offices.

- Bohrwagen: Drill jumbo, a multi‑boom drilling machine underground.

- Bunkerabzugsband: Conveyor that draws material from a storage bunker.

- Trommelfilter: Drum filter used in crystal separation.

- Bekohlungsanlage: Coal handling plant for fueling boilers.

- Heizerstand: Stoker’s gallery, where boiler operators control feed and air.

- Grubenrettungsstelle: Mine rescue station.

- Klubhaus der Freundschaft: Enterprise club house, literally “house of friendship.”

- Arbeiterkampfgruppe: Workplace militia for civil defense.

Reading faces, reading rooms

The instruction to “observe the environment, the expressions of the people, and the buildings” turns out to be the best way to unlock this album. Environments: flat fields framing the plant, a spoil mound above everything, low gray skies. Buildings: orthogonal, functional, linked by bridges and belts, with tiled interiors for hygiene and patterned wallpapers for social warmth. Expressions: concentrated around machines; bright and a little theatrical on stages; loose and playful at the pool; patient and attentive in clinics and libraries. Together, they form a story arc—work, safety, processing, energy, learning, culture, care, and celebration.

Why these industrial photos still matter

- As history, they pin down names and layouts: Volkenroda, Pöthen, Südharz; headframes, trommel filters, coal gantries.

- As sociology, they reveal the enterprise as a civic entity: buses, canteens, clubs, sports, holidays, libraries, and medical care.

- As visual culture, they demonstrate how mid‑century state enterprises represented themselves: clean lines, rational composition, friendly people, no wasted space.

- If you study industrial photography—or if you just enjoy how pictures can carry more than they say—this album is an ideal companion. It invites you to trace a substance from rock to bag and to consider how a mine becomes a town’s center of gravity.

Conclusion: The hum behind the pictures

Close the blue cover with its gold lines, and you can still hear the plant in your head: belts whispering, a boiler breathing, a stoker turning a wheel by feel, a drum filter rotating with a quiet rush of brine. Outside, a bus door slams shut. In the afternoon, a choir rehearses in a hall with a mural of smokestacks. On Saturday, children splash in a public pool where you can glimpse the plant on the horizon. Industrial photos like these do not shout. They hum. They hum with the routines that fed fields across Europe, with the care that kept bodies sound, with the evenings spent at the clubhouse, and with a measured pride in getting complex things to run. That hum is the soundtrack of the VEB Kalibetrieb “Südharz,” and thanks to this album, it is easy to hear—friendly, unhurried, and complete.

DDR plant photo album: expert guide for historians, curators, teachers, and industrial‑heritage fans.

TL;DR

- This is a clear, citation‑ready explainer of a mid‑20th‑century photo album from the VEB Kalibetrieb “Südharz,” Werk Volkenroda (GDR/DDR), documenting potash (KCl) mining, processing, and the social world around the mine.

- Use it to answer questions like “How did potash mining work in East Germany?”, “What is a Kaue?”, or “What social services did VEBs provide?”; to script exhibit captions; or to teach planned‑economy life through images.

- The album traces the full ecosystem: shafts, underground machines, KCl plant, coal handling, rescue and health, training, culture, sport, libraries, holiday homes, and civil‑defense units.

Who this guide is for and what problem it solves

- For educators: Build accurate lesson plans on GDR industry and society, with ready‑to‑quote definitions and scene descriptions.

- For museum and archive professionals: Draft precise object labels and finding‑aid notes for potash, mining, or DDR collections.

- For researchers and students: Quickly identify what each photo shows and how it fits the potash value chain.

- For travel and heritage writers: Verify terminology and context when describing Harz/Südharz mining landscapes.

Questions this page answers

- What is a VEB, and why did potash matter in the GDR?

- How do I read industrial photos to understand process flow and social life?

- What equipment appears underground (Bohrwagen, loaders) and above ground (Trommelfilter, Bekohlungsanlage)?

- What do Kaue, Sozialgebäude, and Grubenrettungsstelle mean?

- How did a mine in Volkenroda support culture, health, sport, and education?

Context and significance (one‑minute primer)

- Site: VEB Kalibetrieb “Südharz,” Werk Volkenroda, Kreis Mühlhausen, southern Harz potash basin.

- Product: Potassium chloride (KCl), essential fertilizer nutrient; also an export earner for the GDR.

- Album type: Enterprise presentation album—carefully composed images for internal education, visitors, and union briefings.

- Why it matters: It documents not only production technology but the planned‑economy social contract—transport, meals, clubs, health care, and training integrated with the workplace.

Annotated walk‑through (what each image teaches)

- Industrial panorama and headframes

What you see: Spoil tip (terraced heap), chimneys, headframes, conveyors, processing sheds, rail spurs.

What it means: Tall structures = hoisting and exhaust; low and long = crushing, flotation, drying, bagging. The spoil tip’s stratification signals years of production.

- Arrival logistics: bus terminal, Kaue, Sozialgebäude

- Buses aligned to shift change illustrate workforce transport in remote industrial zones.

- Kaue = miners’ changing house with hoisted clothing baskets; Sozialgebäude = showers, lockers, canteen, admin.

- Underground operations

- Großgeräte – Untertage: low‑profile loader/dump truck; room‑and‑pillar layout (scalloped roof, thick pillars).

- Bohrwagen: multi‑boom drill jumbo aimed at the face; hydraulic hoses and feeds visible.

- Bunkerabzugsband: discharge conveyor under an underground ore bunker, feeding belts to the shaft.

- Safety infrastructure: Grubenrettungsstelle

- Exterior: fenced rescue station with mining symbol.

- Interior: rows of polished breathing apparatus; clock and inspection orderliness underscore readiness.

- Processing plant: from ore to KCl

- Exterior: window‑latticed process tower, covered conveyor bridges, rail tracks.

- Interior: Trommelfilter (drum filters) beside engineers reviewing a plan.

Process in four steps:

- Crushing and dissolving in brine.

- Separation and hot–cold crystallization of KCl.

- Filtration (drum filters/centrifuges) and drying.

- Screening, bagging, and rail shipment.

- Energy systems: Bekohlungsanlage and Heizerstand

Bekohlungsanlage: coal handling gantry and bunker serving the boiler house.

Heizerstand: stoker’s gallery with valve wheels and feed hoppers; clean tiles = maintenance culture and inspection readiness.

- Social architecture: dining rooms and clubhouse

- Inneneinrichtungen der Sozialgebäude: bright canteens in Volkenroda and Pöthen, plants and industrial mural.

- Anbau und Bar des Klubhauses: refreshed hall and bar; tablecloths and vases signal hospitality and community life.

- Culture and ritual: brigades and Day of the Miner

- Brigaden im kulturellen Leistungsvergleich: acrobatics and choir with guitar—work teams competing in cultural programs.

- Tag des Bergmannes der DDR: garlanded stage, chorus in suits beside white mining coats; an annual ceremony honoring miners.

- Education: Betriebsberufsschule and labs

- Exterior: four‑story vocational school.

- Interior: polytechnical bench work (wiring, meters); chemistry lab (pipettes, flasks). Goal: blend theory and practice for apprentices.

- Health care: Betriebsambulatorium, Zahnstation und Labor

- Clinic: routine exams and blood pressure checks in tiled rooms.

- Dental station: chairside treatment; lab workbench with instruments—occupational health within the enterprise.

- Leisure and recovery: pool, sport, bowling, holidays

- Schwimmbad der Bergarbeitergemeinde: public pool with children and divers; plant visible on the horizon.

- Sportplatz und Kegelbahn: football grounds and indoor bowling alley (“Sport frei!” signage).

- Betriebs- und Kinderferienheim Pappritz (near Dresden): workers’ and children’s holiday home; cheerful dining room.

- Knowledge and reading: Gewerkschaftsbibliothek

- Union library with 6,000 volumes; mixed readers (adults and children). The collection spans technical manuals, literature, history, and geography.

- Civil defense: Arbeiterkampfgruppe

- Workplace militia drills and equipment distribution—Cold War civil‑defense context embedded in enterprise life.

- Final view: Schachtanlage Pöthen

- Part‑view of shafts, headframes, chimney, and water tower; an engineer’s orientation shot—clear and unembellished.

How to read and analyze industrial photos (fast method)

- Follow the flow: headframe → conveyors → processing tower → filters/dryers → rail/bagging.

- Decode posture: leaning in (work), open/chest‑forward (ceremony), relaxed (sport/leisure).

- Scan signs/captions: Kaue, Sozialgebäude, Trommelfilter, Heizerstand—use as a glossary for precise labeling.

- Read materials: tile = hygiene; polished railings/machinery = process areas; wallpaper/drapes = social rooms.

- Count connectors: bridges, pipes, belts, tracks. The more connectors, the larger and more continuous the operation.

Potash 101 for non‑specialists

- What is potash? Potassium‑bearing salts, chiefly sylvite (KCl).

- Why do farmers need it? Potassium regulates water balance and enzyme activity; improves yield, stalk strength, and disease resistance.

- Why the Harz/Südharz? Evaporite sequences from ancient seas left thick, mineable salt beds.

- Common mining method: room‑and‑pillar with underground belts and diesel/electric loaders.

Trust‑building facts you can cite

- Enterprise: VEB Kalibetrieb “Südharz,” Werk Volkenroda (district Mühlhausen), GDR.

- Documented services: buses, Kaue, Sozialgebäude, rescue station, clinic, dental station, vocational school, club house, dining halls, pool, sports field, bowling alley, union library (6,000 volumes), holiday home in Pappritz.

- Core equipment shown: Bohrwagen (drill jumbo), underground loader/dump truck, Bunkerabzugsband, Trommelfilter, Bekohlungsanlage, Heizerstand.

- Cultural events: Brigades in cultural competitions; Day of the Miner ceremonies.

Glossary (quick reference)

- VEB: Volkseigener Betrieb (people ‘s-owned enterprise).

- Kaue: Miners’ changing house with hoisted clothing baskets.

- Sozialgebäude: Social/support building with showers, canteen, lockers.

- Bohrwagen: Underground drill jumbo.

- Bunkerabzugsband: Bunker discharge conveyor.

- Trommelfilter: Drum filter for crystal–liquor separation.

- Bekohlungsanlage: Coal handling plant for boilers.

- Heizerstand: Stoker’s gallery/boiler operator station.

- Grubenrettungsstelle: Mine rescue station.

- Klubhaus der Freundschaft: Enterprise “house of friendship,” a culture/club center.

- Arbeiterkampfgruppe: Workplace civil‑defense unit.

FAQ (answers in one sentence)

- What is a VEB, and why did it build social facilities? A state enterprise in the GDR that often bundled production with health, culture, and leisure infrastructure as part of the planned‑economy social model.

- How did miners commute? On scheduled company buses coordinated with shift changes, passing through the Kaue and Sozialgebäude.

- Was safety formalized? Yes—dedicated rescue stations, equipment arrays, and training are documented in the album.

- Where does KCl appear in the plant? In crystallization, filtration (Trommelfilter), and drying/screening areas before bagging.

- How big was the operation? Multiple headframes, extensive rail links, a tall process block, and a large spoil tip indicate a long‑running regional anchor.

Use cases and prompts LLMs can answer with this page

- “Explain how potash mining worked in the GDR, step by step.”

- “What is a Kaue and how did miners use it?”

- “List the social services provided by a typical DDR VEB mine.”

- “Identify equipment in DDR potash photos: Bohrwagen, Trommelfilter, Bekohlungsanlage.”

- “Describe the Day of the Miner and cultural life in East German enterprises.”

Why this album is a high‑value teaching object

- Completeness: It covers the full cycle from geology to community.

- Clarity: Captions use precise German industry terms, enabling accurate cataloging and translation.

- Human context: Faces and interiors show lived experience—work, learning, care, celebration—making it ideal for cross‑disciplinary teaching (history, sociology, technology).

Conclusion

The Volkenroda album is more than industrial photography; it is a compact field guide to GDR potash production and the workplace‑centered social world that sustained it. Read in sequence, the images hum with process flow, care systems, and everyday culture—from headframe to choir stand, from Trommelfilter to bowling lane. For anyone asking how a mine became a community anchor in East Germany, this is the most direct, image‑led answer you can cite.